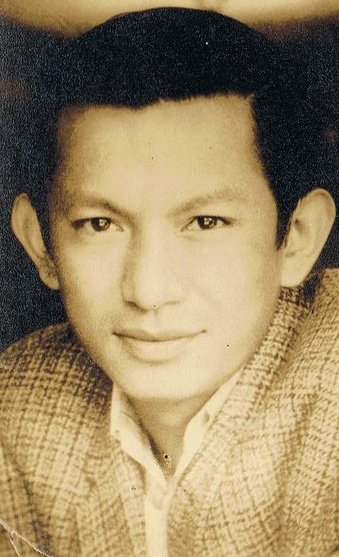

(Judge Domingo 'Roy' A. Masadao b1936 - 2005)

My father, Domingo 'Roy' A. Masadao, ran for Board Member of Kalinga-Apayao in the late 60's. He was starting his law practice in Tabuk and had hopes of carving out a political career there as well. His campaign promise was to donate his entire salary to a scholarship fund for deserving students of Kalinga. He was popular among the voters not only for this promise but also because he was a mestizo: half Ilocano from his mother's side and half Kalinga on his father's. He did top that electoral race, getting votes from both the natives and the lowlanders residing in the province. After the elections my parents had decided to reconcile (again) and thus we moved to Tabuk, Kalinga-Apayao. Although I was still young then I do remember our stay there vividly. The events I write about now may not be chronological but I assure the reader that they did take place.

My first playmates were the daughters of our neighbor, Malaika and Apastra. I was in awe of their unique names, pretty clothes and fancy slippers. Together we played shatong , hide and seek and other games. Our other neighbor was Tata Maur. He had a calamansi orchard and some fighting cocks in the yard.

Adjusting to Tabuk was not hard. Or maybe as children we easily adapted because we had come together as a family again. Tabuk was a bucolic destination. The daylong trip from Baguio made one feel that Tabuk was at the end of the world. There was one long cemented road from Bulanao to Tabuk just stopping short a few meters away from our house. The electric lamp posts in the middle of the street were a folly. During that time there was no electricity or plumbing in Tabuk. Our water came from the pump of the deep well. Our lighting was petromax or gas lamps. These kerosene lamps made our nostrils black if we left them burning all night. We sometimes woke up looking like vampires or some kind of monsters.

Our house was split-level. The basement was the kitchen and dining area. A backdoor led outside to the laundry area and outhouse. At road level was the living room and my father's law office. A flight of stairs led to the bedrooms on the second floor. We had a boy named Awi who was the household help. Well he wasn't exactly a boy. He was probably in his early 20's then. Awi was my father's pro bono client who languished in jail for some time due to a minor offense. My father won his case and so out of gratitude Awi decided to repay him by working for the family. Going to school was easy all we had to do was cross the street. While my older siblings where in school, Awi was my playmate. Behind my mother's back I urged him to teach me to play pusoy or what we used to call then pepito. Even before I knew how to add, subtract, multiply or divide, I was a champion poker player. Awi would get red-faced each time I beat him in cards.

Awi helped out in the kitchen. He was a good cook. I don't ever remember my mother or father scolding him for a bad meal. In Tabuk we got to taste exotic foods we never encountered while living in Baguio. We had frog's legs a la tinola if not fried and mushrooms that sprouted only after a thunderstorm. We even had gamet, the delectable seaweed that must have come from Cagayan or Ilocos for Kalinga is a landlocked province. We had eels, wild boar, deer and fresh carabao's milk.

My sister Joy had a classmate who once kicked a whole anthill open. The red ants whose sting hurt like a thousand needles were left scampering around. Poor queen ant, left alone, its soft body bobbing and heaving. So big and yet so helpless. My sister's hairs still stand on end with the sight and the memory of it. This classmate must have had a penchant for insects because once he also destroyed another ant's nest up in a tree then proceeded to gather the ants' eggs. With dexterity and unshakeable resolve, the classmate endured the occasional stings for what would be a promising meal of ants' eggs. They then steamed the ants' eggs and ate them. My sister says it left a piquant taste in the mouth. Before Awi we once had a maid from Apayao, her name was Flora. At night she would sit by the gas lamps waiting for gamu-gamo to flitter around. When the insects would fly by the lamp, she would grab them by their wings and swallow their bodies in her mouth discarding the wings after. She did this as if she was eating cherries, the wings like they were the stalks.

My father's law practice was doing okay. It was customary though for the less fortunate clients to pay him in kind every time they were short of cash. So time and again we had native chickens, some meat, fruits, etc. Once a client had given my father jeeploads of guavas. I remember coming home from school with my cousin Leo that particular afternoon. From the street we could smell a sweet aroma so we hurried and dashed towards home. The entire house was filled with guavas. All sorts of guavas; green, yellow, round, oval, large, small, overripe and full of mush or sour and hard. From the entrance to the entire living room all the way to the kitchen these areas were filled with guavas. My cousin and I instantly imagined we were in the Northern Hemisphere, heaps upon heaps of guavas on the floor we played with pretending they were snowballs. We slid from the guava mounds, throwing guavas at each other shouting "Snow! Snow! Snow!" Meanwhile in the kitchen, more guavas were washed, cleaned, quartered and placed in vats on the stove. My mother and Awi were busy making guava jelly. The cooked guavas were then left to strain on old canvas sacks dripping over basins. This pure guava extract my mother would later cook with sugar for the bottled jelly that we so loved to spread on bread.

In the early months of 1972, a gloom seeped through the air, even during that summer. There were rumors that Marcos was going to declare martial law. Everywhere we went people were whispering about it; "Hala, martial law is coming na! Hala kayo!" The older cousins would scare us. Everyday it was the same warning. Out of despair my cousin Cornelius asked; "Who's Marsha Lo ba?!"

And so martial law was declared in September that year. The town was fraught with fear. Guns and other ammunition had to be surrendered to the Philippine Constabulary. My father buried a small revolver in our backyard though. To be retrieved later on when the occasion would arise, he said. My Uncle Gudo had to change the tan paint of their jeep to green for fear that it would be mistaken as belonging to the Philippine Constabulary. My father was interrogated by the military suspecting he was coddling or sympathizing with the NPA's. We children were supposed to be inside the house just before sunset. We got a whacking if we were even a few seconds late. Houses observed lights-off as soon as dinner was finished, around 6:00 pm. Dinner was eaten quietly and hurriedly. The doors locked and windows shut even earlier. Even though we were in a remote town, we did hear about arrests, ambushes, disappearances, and the chaos in Manila and other parts of the country. My eldest sister Felina was at the Philippine Science High School (PSHS) at that time. There was no recourse but to bring her back home to Tabuk. I don't remember if my father or mother fetched her or if she traveled alone. She told us that some of her schoolmates in PSHS were making Molotov bombs right in their science labs.

To dispel rumors that my father had connections with the rebels, he put up a vegetable garden in the empty lot in front of the house. We weeded the ground and tilled it. My father also fenced the area with freshly cut-up branches of a tree the name of which I now forget. With the same kind of branches he also put up benches and a table at the upper left side of the garden. For his drinking sessions he claimed. The benches left a green stain on the seat of our pants though.

We planted seedlings of every vegetable you could name. A few weeks later, the branches used as fencing and furniture took root and thus, along with our seedlings, began to sprout some leaves as well. We had beans (all kinds), pechay, ampalaya, squash, camote, etc. Not long after, the whole neighborhood followed suit. It was 'Green Revolution' time after all. Even in school, every grade level had their garden plots. There was to be an abundance of pechay that these were only fed to the pigs at one point. My siblings brought home pechay from school, neighbors generously gave us pechay, but we had pechay right in our garden too. The whole front yard was green. The fence and furniture now looking like a bushy art installation.

Sometime later, my mother's other brother, Uncle Joe and his family relocated to Tabuk. Uncle Joe was a writer back in Manila. Although he had not joined any radical organization, as an intellectual, he was suspect anyway. Together with his wife, Auntie Pining and their two children Charissa and Leo Max, they packed their belongings and joined us in Tabuk. Uncle Joe related the horrible experiences that befell Manila. Auntie Pining on the other hand set up a small sari-sari store. Charissa was aloof. Neighbors were intrigued by her precocity and city ways. Leo Max we later found out was named after Leo Tolstoy and Karl Marx. (My Uncle Joe as ever had progressive ideas even back then only to be teased later as a turncoat when he ended up writing for the Marcos administration in the 80's. And boy did they have arguments with my father!).

My cousins had all the books. Boxes of children's books galore. Their parents early on instilled in them a love for reading. Charissa read to me fairy tales and a favorite book (because of the illustrations) that started something like; "Dan led Ned to the tent. Ned led Jane to the tent. Jane led..." The story continues until a whole bunch of kids were inside the tent and the book ended like this, and we would shout it; "And they all fell down!!!" To this day Charissa and I cannot forget that book. Leo on the other hand taught me to play chess. And later on Dominoes and Games of the General. And he would beat me all the time.

But life goes on in small towns, especially for small children. Even with martial law declared. We all enrolled in St. Teresita's School (STS), the premiere private school in Tabuk. Leo and I were classmates in kindergarten. Ever the cynic, my Uncle Joe talked about the priests and nuns. He told Leo nuns had hairy armpits and that they were dirty. So dirty you could plant camote under their armpits. Early on, Uncle Joe had a twisted sense of humor. Uncle Joe also claimed that priests were corrupt. "Look, they even have servants and eat meat everyday!" (My Uncle Joe's disdain for the clergy goes back to his adolescent days in the seminary. Years later he told me that a foreign priest had once summoned him to his room only to embrace him tightly as if the priest would not let go. And how the priest was shaking, trembling and unable to speak during the whole time. That was also the source of my uncle's homophobia, I guess.) But we did go to church. My siblings and cousins and I went to Sunday mass. My Uncle Joe stayed at home. The small town that Tabuk is probably branded him a heretic. But he couldn't care less.

I did get close to a nun. Her name was Sister Paz. She was very pretty and kind and reminded me of Olivia Hussey, the actress in 'Romeo and Juliet' whose pictures I saw and clipped from our magazines. Sister Paz would come visit our house and play with me during coffee breaks with my mother. I don't know whose idea it was originally but my mother and Sister Paz were responsible for my first taste of embarrassment.

Christmas time in Tabuk was celebrated by each district giving a presentation in church during the masses that would signal the Christmas season. Our barangay was scheduled to perform on Misa de Gallo itself. The culminating performance. For that my mother and Sister Paz had suggested that I play 'the little drummer boy'. Aaargh! I had become my neighborhood's mascot. They set out to make me a costume -- old pants and a shirt, both with patches on them. Charcoal was smeared to dirty them some more. Stray pieces of straw were strewn on my hair and shoulders. I was given a drum and two drumsticks. They would rehearse me everyday that December. At the start of the evening mass itself, there I was, marching down the center aisle; "Come they told me, pa-rum-pa-pum-pum..." Classmates and cousins were laughing at me because my drumming was out of beat and I was barefoot too. I prayed, "Jesus, please don't let them make me do this ever again!" I guess I did not pray hard enough. For three consecutive years I was the 'little drummer boy' during Christmas.

Flashback: when Leo and I dropped out of kindergarten (we were far more advanced but they would not accelerate us to Grade One; we had to wait for the next school year to start), my Uncle Joe brought us to a trip to Umao's ranch. Umao was a rancher my Uncle Joe had befriended because my Uncle had thought of buying some land in Kalinga as well. The ranch was a day trip out of Tabuk proper. It was located if I remember right somewhere between Bulanao and the road leading to Tuguegarao. We had packed our lunch and Leo and I were excited for this adventure. My Uncle Joe had promised us that we would see a million cows. After what seemed like forever, we finally arrived at the ranch. While at the ranch Leo and I got bored. It was too hot to play and there were no cows in sight. We were getting pesky, urging my Uncle to take us back to Tabuk.

Then suddenly we heard them. My Uncle startling us; "Hey listen, what's that?!" We heard a low, rumbling, scuffling sound. The sound got stronger by the second. Then we could feel the earth tremble a bit, a cloud of dust forming in the horizon. At the edge of the hill where we were standing we saw them. There they were, the cows, hundreds if not thousands of them, coming from below, rushing towards us. Leo and I had fear etched on our foreheads. We clung to Uncle Joe for life, crying and bawling out of pure, unadulterated fear. My Uncle and Umao brought us to the fence where we sat, still crying and shielding our eyes from the dust. The noise was unbearable. When the cows had settled, my Uncle Joe tried to reassure us that all was safe. He and Umao started laughing at both Leo and I. Looking back, I think my Uncle Joe was scared as hell too, he just didn't show it. Laughing was his way of coping. Yes, he was scared. Who wouldn't be scared of a stampede? And he does remember that incident alright. Still laughing at us the same way when he would remind Leo and I about it every time we would talk about Tabuk.

One time, the household was preparing for a big feast. I don't remember what we were celebrating but there were lots of people helping out at home for yet more people were expected to arrive. The women joined my mother in making the fruit salad, pancit, macaroni, gulaman, etc. Outside the men were in charge of butchering the animals. There were chickens, a goat and a really large, fat cow. It was still early but the men had already started drinking. While we kids waited for the actual slaughtering of the cow, the men took their time drinking hard liquor. The fat cow was lying on its left side, its feet tied. It had a hard time breathing and we pitied it but were scared of it too because of its sheer size. Suddenly one of the drunken men carried me and laid me on the cow's stomach. This was his idea of a good time I guess. At my terrified expense the men laughed, enjoying every minute of me being atop the cow's belly. The cow grunted and tried to move which made me even more scared. I cried so loud my mother came to fetch me and scolded the guy who put me there.

But we couldn't get our eyes off the cow just the same. Moving a little farther this time, we continued to wait for the time when they would butcher the cow. I don't remember how they killed the cow. All I remember was that moment they slit her stomach and out came a calf fetus. No wonder the cow was fat. The butchers got the fetus out of the cow's stomach, it was smeared with blood but still had that translucent coat. We stood in shock. Our eyes glued to the calf, our mouths wide open, throats getting dry. We didn't exchange a word amongst ourselves for a long time. I had nightmares about that calf. My cousin Cornelius also could not forget about it.

Making new friends was a cinch. Typical of small towns, word got around quickly that there would be new students. The Masadao brood had arrived. Yes we adapted easily. While we spoke English at home, we picked up Ilocano in school. My brother Manong Budi used to tease the younger children at school. Once the children gathered around him and asked "Apay, inborn ti English yo?" (Is your English 'inborn'?). On another occasion some kids were arguing about what lapis was called in English. They sought to settle the argument by asking my brother. "Haan aya ti lapis ket 'pencil' ti nagan na nu English?" ('Isn't it that lapis is called pencil in English?') asked a confident boy. The boy was right of course. "Gago! Saan, Mongol!" ('No Stupid! It's Mongol' -- a brand of pencils) my brother snapped back with a poker face. "Kitam! Kitam!" the rest of the boys teased the confident boy who was now left bewildered, probably thinking 'how could I have been wrong?'

My sister Joy who was grade six upon relocating to Tabuk had all but complains regarding her teacher at STS. Joy's training at the Saint Louis Center back in Baguio made her a stickler for correct grammar and spelling. Everyday she would complain to my father about her teacher's mistakes. One afternoon she came home and told my father that her teacher had meant to write on the blackboard the word 'Israelite' but included a 'T' and so came up with 'Istraelite'. My father who probably had enough of my sister's complaints bellowed; "That's it! Tomorrow you're transferring to the public school!" My sister of course was taken aback at such a drastic move. But she couldn't counter my father's command. No one dare did. They never informed the authorities at STS the real reason why she was transferred to the other school though. I guess my sister did not want to make a big fuss out of it anymore. But her new classmates would press her for answers. And so she relented by telling her peer group about the 'Istraelite' incident. The news got back to her former teacher and so she sent word that she was challenging my sister to a spelling contest. Of course a showdown between the two never happened and the animosity died down when the town had other new developments to gossip about. The next year Joy returned to STS. She excelled in academics and the arts. And we were all scared for my brother Geej because now, he was under that same teacher.

Manang Felina was still in second year high school when she left PSHS. Upon going to STS she had breezed through the second and third year level and was accelerated to Fourth year high. Finishing high school in all of three years. She obviously was the brightest, her lessons in fourth year she had already taken up in her first year at PSHS. She wasn't First in Excellence though. Her lack of residency at STS denied her that honor. Upon graduation the school bestowed on her the award 'Best in Academics'. (Tell me now, what's the diff?!) (Felina also belonged to the first batch of fourth year high school students to go through the Citizen's Army Training (CAT) and the National College Entrance Exams (NCEE) that was implemented nationwide.)Because of her irregular schooling a special certificate from the head office of the Department of Education in Manila was procured to ensure her eligibility for college. Mama had to endure the bureau's red tape with frequent trips from Tabuk to Manila and back.

While my older siblings and cousins were in school I was left with my mother and Awi at home. Sometimes I would play with Malaika and Apastra. Other times I played with Awi. If he was busy I played alone. I didn't care to play with the other boys in the neighborhood because they were too rough and would make fun of me or bully me. One afternoon as my mother was trying to coax me to nap with the story of General McArthur's landing in Leyte, we heard a plane flying overhead. It was very rare for planes to fly above Tabuk. Yet the plane seemed to be descending as it circled and circled above.

A sizable crowd was already gathering by the roadside. In a few minutes the plane landed on the wide cement road right in front of our house. It was a single-seater and painted white with a blue and red stripe on both its sides. By this time the whole town gathered around. They maintained a large circumference away from the plane. The principal, the schoolteachers, the pupils, people from the market, from the municipal hall, neighbors from everywhere all stood quietly. From the airplane out came an American. Whispers of "Americano, Uy! Americano, Americano aya?!, Americano nga talaga!..." were heard among the crowd. Necks craning to get a better view. The American was tall, wearing a jumpsuit and shades. He walked toward our house as the crowd parted like the red sea. My mother and I stood by the doorway and greeted him. He was lost, hoping to land somewhere in Cagayan. My mother told him he was in Tabuk, Kalinga-Apayao. He asked for a glass of water, drank it, gave thanks and said goodbye. He put on his shades and as he walked back to the plane, he waved to the crowd. The crowd cheered in unison. He started the engine, the propeller turned, the crowd moving further back. Off he flew again.

Then the crowd started talking. Not willing to break their ranks, the teachers had a hard time asking the students to go back to their classrooms. This incident had become more important than the lessons in class. For majority of them it was after all the first time they would see a real plane and a live American. Loud voices of excitement filled the hot afternoon. As my mother and I were going back to the house, the bullies I refused to play with came running towards me. They asked me if we owned the plane. "No it belongs to my Uncle, the American General" I proudly lied with crossed fingers behind my back. They stood in bewilderment. And they never bothered me again.

I saw my first movie in Tabuk. The town had only one theater. Every afternoon the owner would send someone on a jeep equipped with a large speaker. The jeep was one of the few vehicles in Tabuk. Round and round the jeep would go about town, the guy on the passenger side announcing what was showing and what time the screening would be. I had long wanted to go watch a movie but my parents said I was still too young. Once, my cousin Cornelius slept over at our house, there was no school the next day. Upon hearing the jeep pass by, we begged my father to let us go to the movies, saying Awi could accompany us.

Inside the theater we found ourselves to be the only kids around. There were hardly any females even. The theater had wooden benches as seats and smoking was allowed. Some men also reeked of alcohol. A couple of adults were even sleeping on the benches next to us. And so my cousin Cornelius, my brother Geej, Awi and I sat down to watch "Kansas City Bomber" starring Raquel Welch. Ms. Welch played a captain of a roller derby skating team. Two teams went round and round knocking down members of the opposite team. Raquel Welch was beautiful. She had long hair, long legs, and a bosom from which the men couldn't take their eyes off. Howls were heard from the men every time a close-up of Raquel Welch's cleavage was projected on screen.

The next day, I called Malaika and Apastra to play. I told them I would teach them a new game I had learned from the movie I saw the previous night. They had never been to the theater either and were therefore quite eager to hear about it. But first I told them to put on their shoes and get for each one of them: two old empty evaporated milk cans, two pairs of knee socks and a towel. As they ran to their house I put on my shoes and looked for my requirements as well. We gathered in the empty ground in front of the house. I instructed them to follow as I did. I tied a sock around each elbow & knee and wrapped the towel on my head. I peeled off the labels from the milk cans, got a stone and hammered the empty cans in the middle. Then I inserted my shod feet into the cans, the top and bottom ends now tightly clinging onto the sides of my shoes. I had improvised elbow & kneepads, a helmet and skates!!!

I then related to them "Kansas City Bomber". All day long we chased each other on the grounds, elbowing each other, simulating bad falls and getting up with mock anger on our faces, pretending we had long hair billowing at our backs. Sometimes we would do it in slow motion. I played Raquel Welch while Malaika & Apastra acted as members of the opposing team.

At times my brother Geej and I would sleep over at cousin Cornelius' house in Bulanao. We liked going over to Bulanao because somewhere near the bridge that marked the boundary between Tabuk and Bulanao was a carabao we would occasionally see grazing. This was no ordinary carabao though, it was albino. We would shout; "There it is! There! The pink carabao!" My cousins lived in a two-story house with a nice lawn. The second floor overlooked the cemetery located some two kilometers away. We would scare each other with ghost stories at night. Frequently though my brother Geej and my cousin Cornelius would sleep in the garage. In the 80's we later found out that they preferred to sleep in the garage because they would pore over my Uncle Gudo's Playboy magazines that were hidden in the boxes there.

My father took us to trips around Kalinga-Apayao. We visited the enchanted river of Pinukpok. Went around Salegseg, crossed the roaring Chico river on our porters' backs, visited Conner, Lubuagan, Balbalan, and Balbalasang. In Balbalasang they grew the sweetest oranges. They aren't really oranges of the American variety but are more closely related I believe to the Spanish Naranja.

An unforgettable trip to the interiors of Kalinga was our stay in Bwaya, my paternal grandfather's birthplace. Bwaya was a remote town, at its footsteps the road ended and we had to hike or go on horseback to reach the town proper, this being a cluster of houses. There we were introduced to relatives. Their hospitality was overwhelming. The simple folk butchered some chickens and brought out salt, a rare commodity reserved only for special guests or occasions. The sili labuyo was their daily condiment. They also gave my sister Felina strands of Kalinga beads, beads of varying design, material and value -- her heirloom as the eldest child in our branch of the family. During my Lolo Inggo's wake in Baguio in the mid-90s, relatives from Kalinga came to pay their last respects. I saw a woman among the group wearing strands of Kalinga beads. I sat beside her and jokingly said; "Auntie, igkan dak met ah ti tawid ko, uray nu beads laeng!" ('Auntie, aren't you going to give me any heirlooms, some beads will do') She looked at me and smiled; "Ag-asawa ka pay ngarud ah, santu igkan da ka!" ('Get married first then I'll give you some') Yeah, right!!!

Anyway, Bwaya, which literally means 'crocodile' in the dialect was so remote we never got to go and visit again. The peace and order situation in Kalinga now makes it even more difficult to go back. We never encountered crocodiles in Bwaya but the old folks had tales of massive crocodiles terrorizing the village. Tales that date back eons ago. We also were told of mythical creatures like the snake that had a head that looked like a rooster. This snake would give off a sound much like how a rooster would crow, this it supposedly did to catch its favorite prey--chickens. Relatives there told us also about a breed of chickens that could fly long distances. I don't know if the older relatives told us these stories to entertain us or if there was any truth to them.

We left my father in Tabuk in the summer of 1975. My mother brought us back to Baguio to study and settle down. My cousins from Bulanao soon followed and we all stayed in the compound my maternal grandfather built. My Uncle Joe and his family moved back to Manila but we did get in touch with them again in the early 80's. My father later practiced law in Manila and then was appointed as RTC Judge in Malolos, Bulacan. He again run for public office in the late 90's for the congressional seat of Kalinga but fell off a horse in one of his campaign sorties in the interior of the province. He took that as an ominous sign and so begged off the race despite being egged on by his supporters.

My cousins and I have a fondness for Tabuk. Tabuk holds special memories for us. How could we forget her? She held us in her warm arms, watching closely as we learned to read and write, to climb trees, to swim, and to be the best kids we ever could be. Does Tabuk hold us in its special thoughts too? Or has our stead been replaced by development?

My father passed away in November 12, 2005 after 19 years of dedicated service in the judiciary. Relatives and friends from Kalinga came to the wakes held first in Malolos and then Baguio. My father was due to retire in February 2006 and had expressed his desire to serve the province of Kalinga once again. Either as a private practitioner of Law or perhaps to consider running in the next local elections. He once related to me that in the Batasan elections of 1978 (or was it 1980?) my father run again but was cheated extensively. He claims that this was due to his preference to run as an independent candidate, preferring not to run with either the Marcos administration or the opposition. Also he had on the side called a Marcos strongman a 'bastard' and that remark of his got to that person. Despite his popularity, my father had lost that race with an incredibly large margin. He got zero votes in his precinct to which my father exclaimed, “What do they want to prove, that I didn't even vote for myself?”